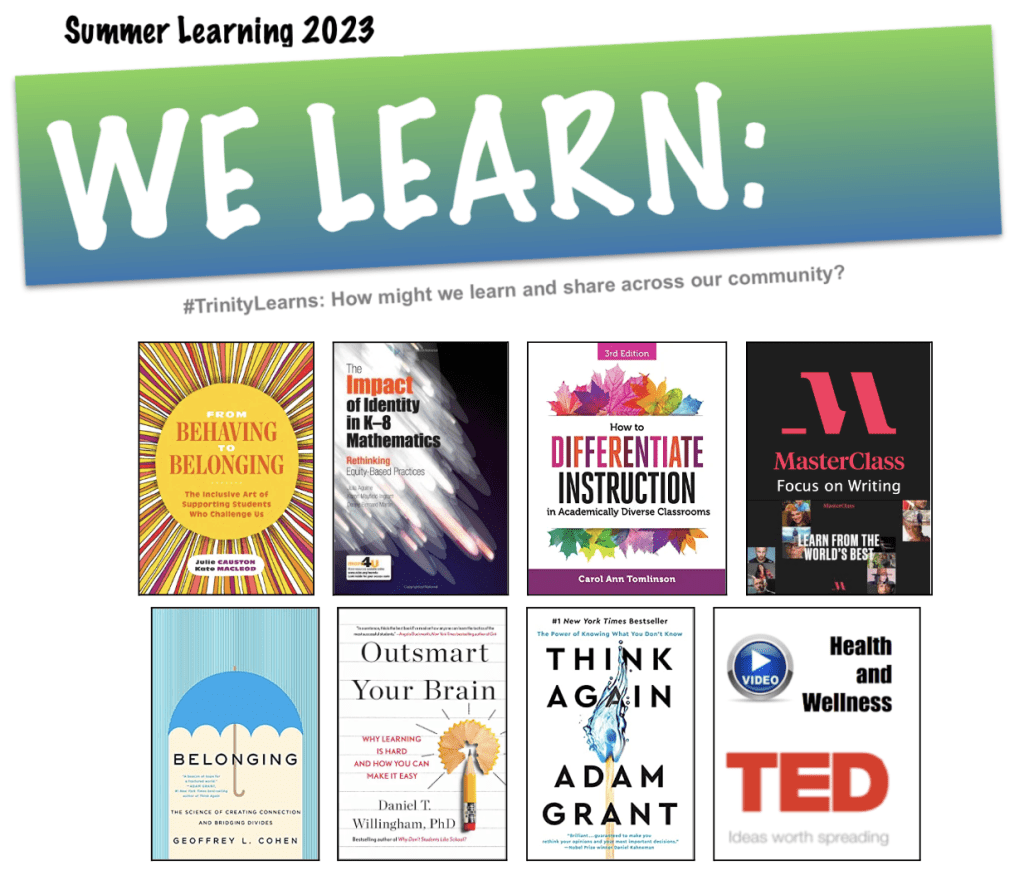

If you would like to read summaries and reviews of the books above, please follow the provided links:

- From Behaving to Belonging: The Inclusive Art of Supporting Students Who Challenge Us by Julie Causton, Kate MacLeod

- The Impact of Identity in K-8 Mathematics: Rethinking Equity-Based Practices by Julia Aguirre, Karen Mayfield-Ingram, Danny Martin

- How to Differentiate Instruction in Academically Diverse Classrooms by Carol Ann Tomlinson

- Belonging: The Science of Creating Connection and Bridging Divides by Geoffrey L. Cohen

- Outsmart Your Brain: Why Learning is Hard and How You Can Make It Easy by Daniel T. Willingham

- Think Again: The Power of Knowing What You Don’t Know by Adam Grant

If you would like to know more details about our curated TED talks and MasterClass selections, please follow the provided links:

- MasterClass: Focus on Writing with Malcolm Gladwell, Judy Blume, R. L. Stein, Roxane Gay, and others

- TED Talks: Health and Wellness

As you read, listen, and/or watch, we will use the Connect-Extend-Challenge protocol to anchor our Pre-Planning Summer Learning discussions. Use Post-it Notes or jot in your book/journal to think through the following:

-

- How do these ideas connect to what you already know?

- What new ideas are you gaining that extend or push your thinking in new directions?

- What ideas challenge you or are confusing to get your mind around? What questions, wonderings, or tensions do you now have?

For Pre-Planning, what are the 3 most important aha’s or takeaways that you would share with others from your selected book/TED talks/MasterClass?