Questions are waypoints on the path of wisdom. Each question leads to one or more new questions or answers. Sometimes answers are dead ends; they don’t lead anywhere. Questions are never dead ends. Every question has the inherent potential to lead to a new level of discovery, understanding, or creation, levels that can range from the trivial to the sublime. (Lichtman, 35 p.)

Spending today as a student-learner has been valuable and interesting. Along with 20 of my colleagues, I spent the day learning about teaching reading using the Orton-Gillingman approach. With zero background knowledge and no experience, I stretched to be considered in the novice category. In other words, this was all new learning for me. While I have heard and seen the acronym REVLOC, it had no meaning to me. It does now.

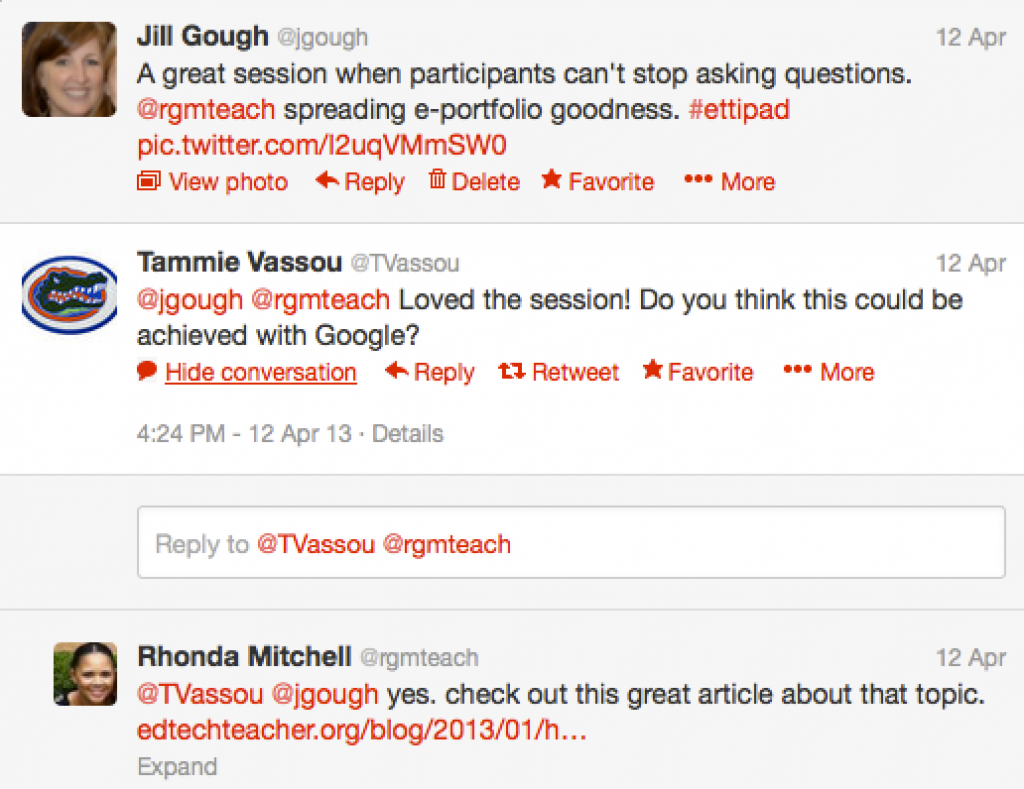

I cannot tell you how many times today a question was asked with the preface “I’m sure this is a dumb question.” It makes me wonder…Do we not see ourselves as learners too? Do we honor and value the questions our students have? Do we honor and value the questions we have?

The seventeenth-century British statesman, scientist, and philosopher, Francis Bacon, who advanced the idea of the scientific method, said “Who questions much, shall learn much, and retain much.” [emphasis added] Centuries later, one of the students quoted in this chapter made pretty much the same argument: “You can’t learn unless you ask questions. [emphasis added] Unless you ask questions, nobody knows what you are thinking or what you want to know.”

If we have asked a question about a subject or concern, we are much better attuned to the information coming back to us. We are, therefore, more likely to retain it. (Rothstein and Santana, 135 p.)

How do we elicit questions from the learners in the room who are not quite brave enough to risk asking a question for fear of how they will be perceived by others? What if we bright spot, value and honor questions? Can we adjust our own thinking and actions to create a community where learning is transparent?

Interrogative self-talk, the researchers say, “may inspire thoughts about autonomous or intrinsically motivated reasons to purse a goal.” As ample research has demonstrated, people are more likely to act, and to perform well, when the motivations come from intrinsic choices rather than from extrinsic pressures. Declarative self-talk risks bypassing one’s motivations. Questioning self-talk elicits the reasons for doing something and reminds people that many of those reasons come from within. (Pink, 103 p.)

What if I ask more questions? Can I teach so that agitation and irritation are the same or at least aligned? What if I structure learning episodes where learners are invited/encouraged/required to ask questions? Can I teach what needs to be learned by listening to and following the path of the learners?

What can be learned if we question our way through an entire lesson? Is it possible to allow students to steer the lesson through their questions? Will listening to student questions help us diagnose, assess and chart a course in real-time? Can we lead learning by following their thinking?

Our educational systems have been constructed entirely around the goal of providing the correct answer to a question provided by an instructor or handed out on a standardized exam. This system provides a form of valid comparison for the results of a group of students, and it provides a foundation of shared information amongst those who have followed a course of study. Unfortunately, the real world, particularly the real world of the coming century, does not and will not work this way. Our heroes are not defined by how well they answered canned questions or what they scored on their SATs precisely because these outcomes do not determine success in real-world situations. The real revolution in education and training, if it comes, will be overtly switching our priority from the skills of giving answers to the skills of finding new questions. (Lichtman, pag. 35)

I argue that we will be able to teach more if we start from our students’ questions. I’ve been told it is impossible to teach what needs to be learned from a starting point of the students’ questions. I’ve also seen the results when brave teachers have put aside their assumptions and tried. See the Kara Leaman’s comment on my blog.

I agree with the idea of interrogative self-talk. How often do I prevent myself from learning, questioning, and risking by the way I reason with myself? Can I change the chatter in my head to be one who questions much, learns much, and retains much?

I assume that we are all here to learn. We function in a learning community. We aspire to be lifelong learners. I aspire to offer my colleagues as much grace and encouragement as I need to learn and grow. I aspire to be patient will every learner when they have questions.

Can I grow into an irritant-agitator practicing the art of questioning?

I aspire to value, honor, and encourage questions from learners.

I aspire to listen more, question more, and learn more.

I aspire to become a falconer.

________________________

Lichtman, Grant, and Sunzi. The Falconer: What We Wish We Had Learned in School. New York: IUniverse, 2008. Print.

Pink, Daniel H. To Sell Is Human: The Surprising Truth about Moving Others. New York: Riverhead, 2012. Print.

Rothstein, Dan, and Luz Santana. Make Just One Change: Teach Students to Ask Their Own Questions. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education, 2011. Print.

[Cross posted on Flourish.]